As a Dominican, there are certain things that I've always understood to be true about our country and our people. For one, we love a good party and will find almost any excuse to get together to dance bachata and drink a few beers. Two, even if not particularly devout, we will implore God in any situation, no matter how trivial, asserting religion as an integral part of our culture; after all, we are the only country with the bible on its flag. And perhaps the most distinguishable, and the most unfortunate, is our refusal to turn our backs on colonialism.

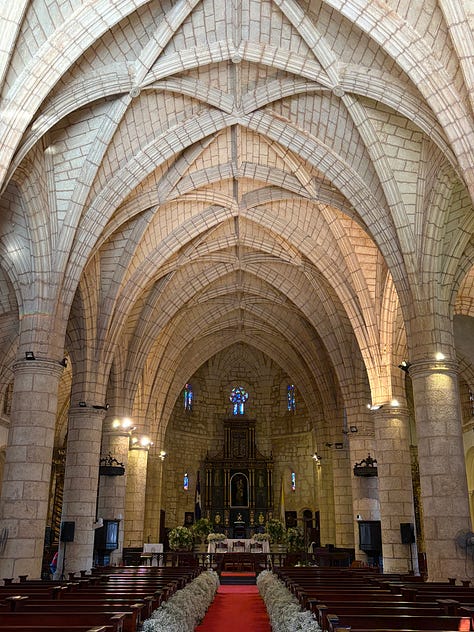

As the story goes, Christopher Columbus and his Spanish fleet first invaded the island in 1492, changing its name from "Quisqueya," as known by the native Taino people, to "La Isla Española," or Hispaniola. The first colony they established was Santo Domingo, the nation's capital. With their language also came their religion, societal norms, and rules of propriety, which have been deeply rooted in Dominican culture ever since.

Earlier this year, I visited my homeland for the first time in eight years. Besides the amazing food, gorgeous beaches, and a family that I’d terribly missed, I was also met with the blatant embrace of a history marred with oppression and racism imposed by the island's first European settlers. But I wasn't so much troubled by the part of town called "The Colonial City," or the Fortress of Columbus, or the Columbus Park, or the large Columbus statue welcoming tourists, but rather by how easily this commemoration of European rule was accepted in everyday Dominican life.

Here in the States, we too have a long and complicated history of systematic oppression and preference for whiteness. But in the summer of 2020, at the height of social unrest, we saw people marching, tearing down symbols of the Confederacy, and demanding that our country confront parts of its ugly history that some would rather ignore. This is not to say that Dominicans lack an understanding of their country's past or the ability to repair what's broken, but it seems to me that instead of turning our backs on colonialism, we have adopted it as part of our collective identity.

And in many ways, it is a part of who we are. Dominicans, at least from my perspective, play along with these rules of propriety that put whiteness, wealth, godliness, and beauty at the helm of all that is considered "good." Even after gaining independence from Haiti in 1844 and then again from Spain in 1861, the nation continues to be subjugated by European standards of living, and one doesn't need to be a student of history to see it.

Take, for example, an artist like El Alfa, who's known for making "dembow" music, a mix of rap and reggaeton. By any other standards, he would be as highly regarded by Dominicans as Bad Bunny is by Puerto Ricans. But taking into account his raunchy lyrics and less-than-wholesome messaging, you'll rarely catch people listening to his music at a typical family gathering. Now, artists like Juan Luis Guerra or Anthony Santos, who sing about love, faith, and overcoming hardship, are revered as masters of their craft. This same uptightness can be found in how people perceive women like Yailin La Más Viral or Tokischa, who strongly challenge, and oftentimes entirely reject, the ideas of piety, humility, and modesty surrounding Dominican women and girls.

The same can be said for having coily hair, often referred to as "pelo malo" or "bad hair," and being dark-skinned, as if the worst thing you can be is Black. Dominicans have been criticized for rejecting, and even looking down upon, any relations to blackness and our Afro-Caribbean roots. Colorism and discrimination are alive and well in the country today, but instead of the perpetrators being white invaders, we are doing the damage ourselves. From stripping the citizenship of almost 200,000 people with Haitian ancestry to a dispute over water rights that led to the closure of the Dominican-Haitian border, it seems as though the Dominican Republic wants to completely rid itself of any connection to their neighbors.

Fear of scarcity, job insecurity, government corruption, and 27% of the population living below the poverty line only adds to the growing tensions between the two countries. Despite our shared experience fighting against the Spanish and French, and the 1937 genocide against Haitians orchestrated by Dominican dictator Rafael Trujillo, no resolution, at least not one asserting dignity and fairness for both people, has been reached.

A country not learning from its mistakes is not a rare tale. America is a prime example of a nation that insists on repeating its painful history. But maybe it's because the Dominican Republic is a country of Dominicans run by Dominicans that makes its attachment to colonialism and its practices somehow worse.

There is a part of me that is resigned to the fact that the Spanish were just a little too good at colonizing, causing the Dominican Republic and its people to be forever plagued by the ideals of European appropriateness. Spanish ancestry is in our blood, Catholicism is an integral part of our culture, and the Spanish language is the only one we've known for centuries. There is no use in denying our history, even the ugliest parts of it, and forgetting won't make it less real. However, embracing the past without trying to avoid the same mistakes is the same as giving up. A country that wants to provide opportunity and prosperity in the future must correct itself in the present. Playing into antiquated tropes and snatching away resources like kids do toys only serves to promote greed and illusions of grandeur, which does nothing for the security and interest of the Dominican people.

It is because I love the Dominican Republic, the place where I was born and have the happiest memories, that I dream of the place it has the potential to be. I recognize that I speak from a place of privilege as a U.S. citizen who doesn't face the difficulties of everyday life on the island and can admit that I am perhaps ignorant of certain nuances. But I still stand firm in my demand for a more just and ethical society, one that treats all people, regardless of their economic status and appearance, with dignity and respect. Most of all, I want to see Dominicans at our best—celebratory, welcoming, hopeful, and headstrong in our belief that greatness can be found when we stand united.